After years of writing, gaming, and writing about games, I recently received my letter to Hogwarts: a job writing for games (like, at a real company! With coworkers! And a desk!). Yes, that’s right: In April of this year, I left a sleepy gig composing ad copy for groceries, waved a (temporary) goodbye to Pennsylvania, and hopped on a flight to sunny foggy San Francisco, to accept a Junior Game Writer position at Pixelberry Studios.

The months thereafter were a blur of writing, coding, and adapting to life in a new city. I lost twenty pounds, took up rock-climbing, found a favorite coffee place, and grieved its loss when I moved home. I’ve seen highs (from the launch of my first chapter to the conclusion of my first game) as well as lows (a gray cloud of homesick ennui that liked to roll in and settle for days at a time).

I’ve also been graciously welcomed into a huge team of some of the brightest and most talented writers I’ve ever had the pleasure of meeting. As someone who is used to being the only “words guy” in the room, it’s been an intensely educational and humbling experience — and it’s got me itching to start blogging again.

So here’s what I want to talk about today:

The complex relationship between a player and their character, and how to approach it as a storyteller.

It’s a topic I’ve thought a lot about over the years, and it’s one I’ve found tends to color my perception of a game as a player. And now that my LinkedIn profile proves I’m a bonafide authority on the subject, I think I’m ready to lay down the law.

That said, I should probably qualify this piece beforehand by saying that the views expressed here are wholly my own (and I could probably find a dozen coworkers who would disagree with any one of them!) The concepts I’ll discuss in this article are, like most “rules” related to writing, more guidelines than anything: another lens through which an artist might think about the tools at their disposal, and troubleshoot obstacles they encounter.

So, with the preamble out of the way, let’s jump right in, and talk about what I’ve come to think of as “The Axes of Roleplay”.

An Overview of the Axes

The relationship between a player and their character is not something that can be easily described. It varies from game to game, and within a given game, can even vary from moment to moment. And to honestly explore it requires a deep frame of reference, not only of the techniques of interactive writing, but of actual games. It’s one thing to understand that Hitman and Zelda approach the player-character relationship differently. It’s another thing to be able to explain why.

Here’s the long and short of what I think:

I think all player-characters exist on a sliding spectrum. At one end of this spectrum sit the blank-slate characters like the Dovahkiin, your WoW character, or the protagonist of most first-person shooters. At the other end of this spectrum sit characters who appear in the game fully-formed—the Solid Snakes, the Clouds, the Batmans. Somewhere along the middle of the spectrum lie characters like Commander Shepherd, Gordon Freeman, and Link. This is what I call The Axis of Definition. It’s the difference between a character you project onto, and a character you step into.

At the same time, I think every meaningful interaction a game presents comments on this player-character relationship (whether it means to or not). And I think that, broadly speaking, the effect of this commenting also falls along a binary spectrum, from “instructive” to “exploratory”. Or, to put it another way, from directive to reactive. In an instructive interaction, the game tells you what to do. In an exploratory interaction, you do something, and the game responds.

For those already itching to object, understand that there’s a reason I say these are “spectrums” rather than “categories” – because I think they’re just that: spectrums. Sliding scales, shaded with gradients, and carrying a lot of messy gray in the middle.

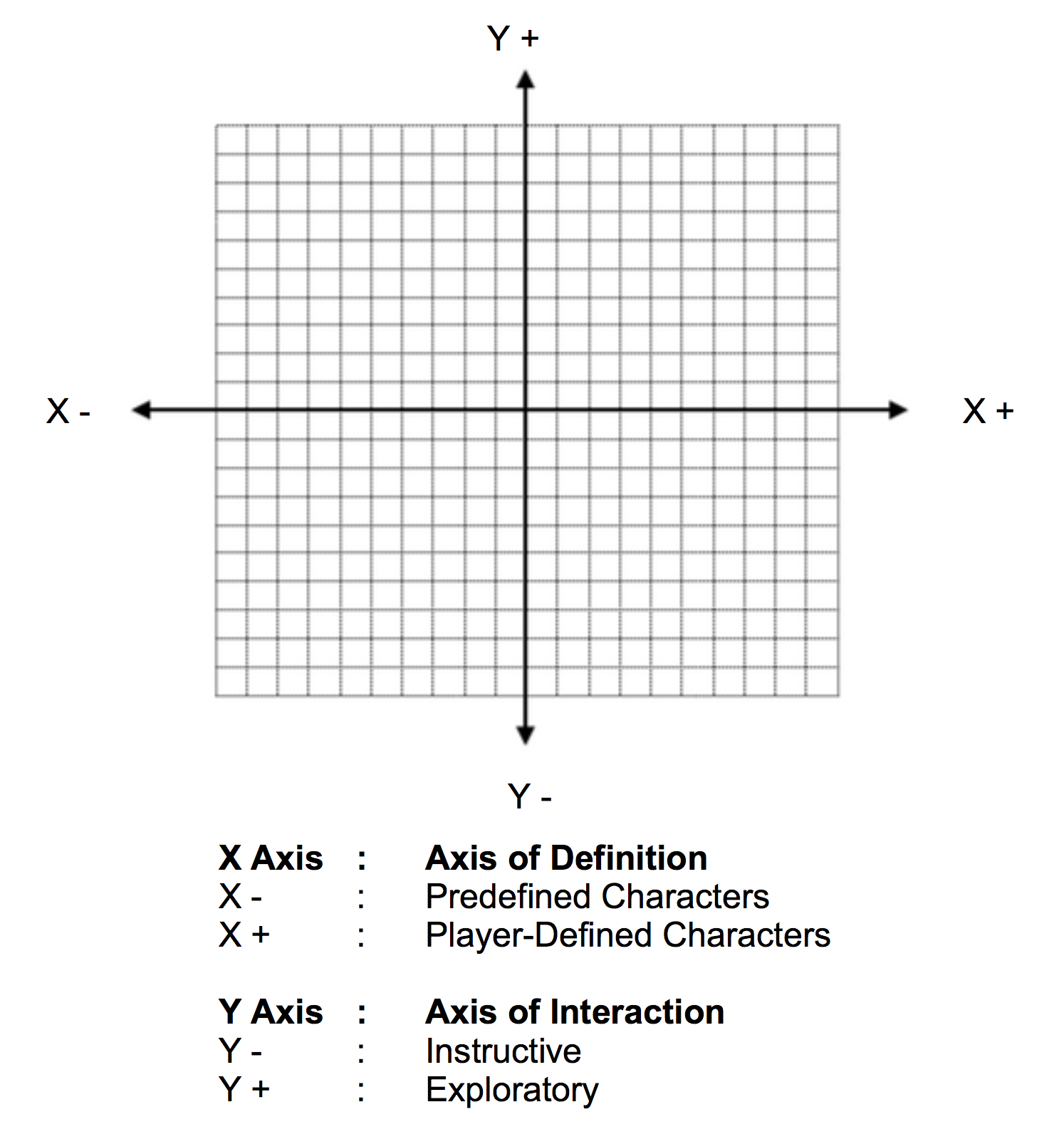

Basically, I think the relationship between player and character looks like this:

A couple things worth noting before we get too deep.

1) THIS IS NOT A CATEGORIZATION SYSTEM FOR GAMES. I think plunking specific games down anywhere on this graph and saying, like, “Skyrim belongs in the top-right,” would be totally misguided and invite a lot of argument. As I’ll get into later, I think a game’s place on this graph changes constantly (literally, with every single moment of interaction). That said, I think you might argue, “Skyrim spends a lot of time hanging out in the top-right,” and make a decent case of it. If anything, I might concede that this is a categorization system for moments in a game.

2) The +/- here are purely referential, and in no way imply some kind of superiority of one approach over the other. I think the freedom to shape the player-character relationship in many different fashions is as essential to a games writer as hues to a painter.

But this is the way these ideas exist in my head, and I’ll be referring to the above graph quite a lot, so get comfortable with it.

Okay, ready?

Let’s dive in.

The Axis of Definition

The Axis of Definition describes narrative aspects of a videogame character — their age, gender, sex, race, creed, personality, background, habits, skills, abilities, and anything else you can think of. This is the meat of the character. It’s the total gestalt definition of who they are — and, more importantly, where that definition comes from.

On the left end of the axis (-) is “predefined” characterization; that is, writing which takes specific aspects of a character for granted, assumes them by default, and sets them in stone well before the player ever picks up the controller. In Arkham Asylum, Bruce Wayne is Batman, an adult male who drives a cool car, dresses up in a suit, and punches bad guys. Those are all predefined aspect of his character, and exist outside the sphere of things the player can influence or change. They are assumed. They are taken for granted. When you turn on Arkham Asylum, you’re tacitly accepting that Batman is Batman and you don’t get to change that.

And not only do you merely accept that Batman is Batman, but the game takes steps to make you feel like Batman. You move like Batman, see like Batman, perceive combat in slowed time like Batman. The entire perceptual framework of the game is designed around getting you to step into Batman’s bat-shoes and walk around in them.

On the other end of the axis, we have “player-defined” characterization; that is, writing or narrative design which grants the player agency over aspects of their character. In Skyrim, virtually all aspects of the character are player-defined. The player decides in the course of play who their character is, from “cowardly Khajiit thief” to “badass Orc barbarian who is also the leader of the Mage’s College because reasons”.

In contrast to Arkham Asylum’s predefined approach to characterization—making the player feel like Batman— a heavily player-defined character has a different goal: integrate and react to the player’s desires and intentions, within reason and within the scope of the game’s fiction, with as convincing a degree of verisimilitude as possible.

It’s important to note, again, that this chart does not intend to categorize games or characters as a whole — only provide context to specific aspects of their writing. Any given aspect of a player-character’s identity can be predefined, player-defined, or anything in between, and various aspects can be defined differently from one another. In Skyrim, for example, some aspects of the character are predefined: namely, that they are the Dragonborn, and a prisoner up for execution.

Yet…why is the character a prisoner?

The game’s answer: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ idk dawg. You tell me!

Broadly speaking, however, a game that tends to hang out toward the left end of this axis is one in which most, or all aspects of the player-character are predefined. Think Solid Snake, Batman, Cloud. Games that tend to hang out near the right side are those in which the player actively defines the character before or as they play: the Dragonborn, Commander Shepherd, etc.

I would also argue that tabula rasa characters who function as little more than a moving camera (say, the player-character in the aptly-named The Witness) exist at the terminal end of the + side. They’re characters who are so player-defined that they’re literally just proxies for the player themselves.

The Axis of Interaction

While the Axis of Definition is largely static in nature—background information that is foundational to who your character is—the Axis of Interaction is more organic, and describes what your character does. It moves and changes; it’s shaped by every moment of gameplay, individually, and by those moments’ sum total.

On the minus end of the spectrum, we have instructive interaction: that is, interaction designed to tell you something about who you are. When Batman gets spotted and the bad guys kick his ass, that is a moment of instruction. It’s the game telling you, “You are Batman, which means you are supposed to be sneaky, idiot. Now go BE BATMAN correctly, or I’ll beat you up again.”

On the plus end of the spectrum, we have exploratory moments: that is, interactions in which a player proactively undertakes an action, and the game organically responds. Take Skyrim’s approach to leveling. Pick up a bow and shoot an arrow? Gain archery experience. Gain enough archery experience? Bada bing bada boom, you’re an archer. You cause your character to undertake an action, and the thematic text of the game responds—either explicitly, or interpretively—by saying, “Okay, that is now a definitional aspect of your character. Acknowledged. Stored. Saved. So-and-so will remember this.”

In either case, the Axis of Interaction is active. It’s the engine that hums at the heart of the player/character relationship and makes the whole thing vroom-vroom-go.

Player-Character Consonance

No matter which end of which spectrum a given game’s characterization tends to prefer, I think the goal of a game (at least most of the time) is to achieve player-character consonance: those moments when the screen falls away, and player and character are one.

In heavily minus-side games, this takes the form of the player understanding how to play as the character the game wants them to be — how to move like Batman, how to think like Batman, how to approach situations like Batman. In return, the game presents the player with opportunities to demonstrate this understanding, and tries its best to mitigate any moments that make the player NOT feel like Batman.

In heavily plus-side games, this takes the form of the game playing back. Plus-side consonance are those moments in Mass Effect when someone acknowledges a choice you’ve made; when a guard in Skyrim says, “Hey, you’re a werewolf”; when the game has successfully cast the illusion of a living, breathing play-space in which you have exactly the freedom of choice you thought you did, and your actions are met with a “realistic” response that is narratively, mechanically, and experientially satisfying.

Consonance, I think, is the narrative equivalent of flow: a positive state that it should be the ideal of designers to ensure both game and character spend as much time in as possible — until and unless it’s thematically important that they don’t.

Player-Character Dissonance

On the flip side, however, is a thing that I think is far more common: player-character dissonance, a problem that plagues games like a virus.

What is player-character dissonance?

Simply, it’s when player and character aren’t on the same page.

In minus-side games, this means an act of betrayal — the game going back on its own instruction, and penalizing you for being the person it told you to be. These are those frustrating moments that make players scream, “I’m Master Chief! You just spent 10 hours teaching me to ruthlessly murdalize aliens; now why are you making me play a stealth section?!”

In plus-side games, this means the sin of omission. Your actions are not acknowledged. Your choices are not recalled. The game implies you are someone or something that flies totally in the face of every available piece of evidence you’ve provided it. “You’re my friend,” says a villager in Animal Crossing, to the player who just spent forty-five minutes hitting them in the face with a butterfly net. “Looting is wrong,” Commander Shepherd moralizes, having looted twelve freshly-murdered alien corpses on the way here.

And now we get down to the heart of this article, and the reason I wrote it: my diagnosis.

I think 95% of the time, when player-character dissonance rears its head, it can be traced back to an inconsistency in how the game approached the axes of roleplay.

Think about it. Any time you’ve played a game and felt suddenly jerked out of lock-step with your player-character, isn’t it the result of inconsistency? When Commander Shepherd speaks too much for himself and says something you don’t want him to, that only makes you mad if you’ve spent 30 hours being educated to expect the opposite. When a TellTale game fails to recall a choice you’ve made, or thinly railroads around either result, that only makes you mad if the game first made a big show of “so-and-so will remember this”. When a fetch-quest-havin character in Skyrim refuses to acknowledge that you’re a god-killing ubermensch, that’s only frustrating if the game has acknowledged a bunch of other choices, and taught you to expect that level of feedback.

So that’s my hypothesis. Now here’s a testing methodology for you:

The easiest way to create a moment of player-character dissonance is to ping-pong unexpectedly around the axes of roleplay.

If you have two choices that trend toward the (+, +) end of the spectrum, then one that veers over to (-, -), you’re gonna have a bad time.

Here’s two interactive examples of player-character dissonance in action:

Http iframes are not shown in https pages in many major browsers. Please read this post for details.Though these are exaggerations, I think they convey my point: moments like these are everywhere in a modern videogame. In fact, as a designer, they can be difficult to avoid. Player-character dissonance might, statistically, be a game’s default state — after all, the larger and more flexible the scope of the interaction you present a player, that harder it is to make that interaction subtextually consistent. This is especially true on any big AAA game with a very large stable of creators. All it takes is one quest-designer not getting the memo to create a game-breaking moment of dissonance.

Achieving and maintaining consonance, on the other hand, is hard. It requires a consistent vision, and a solid understanding of how your game approaches the relationship between player and character. There’s a reason, in the Half-Life series, that Gordon Freeman never, ever, ever, ever, EVER says a word: because that’s a conscious creative decision the team made and stuck to, and violating it halfway through would have been weird and confusing for players.

This is also why choice-driven narrative games tend to either constrict or balloon in scope toward the third act: they either have to create an expansive flowchart of results, to service all possible combinations of prior decisions, or they have to get really tricky with smoke and mirrors, to convincingly seem like they’ve done the other thing.

And that leads us to what many (myself included) might call the most well-known example of player-character dissonance in gaming history: the final decision of Mass Effect 3. Volumes have been written on the subject, so I won’t bother rehashing the same ground — but I think I’ve made my point. If you tell players, “The relationship between you and the character works like X,” but then all of a sudden it works like Y, that whiplash often creates a moment of thematic dissonance that (if it’s egregious enough) can undermine the entirety of a game in an instant.